The ability to deliver exogenous genes in targeted viral vectors for disease modeling is revolutionizing therapeutic discovery. (Wang et al. 2024, Zwi-Dantsis et al. 2025, Haggerty et al. 2019, Naso et al. 2017). The primary advantages of this approach are based on the ability to 1) provide tissue-specific promoters allowing highly specific targeting and 2) over-express or knock-out genes to observe metabolic changes.

The two most popular systems currently in use, adenovirus and adeno-associated virus (AAV), have complimentary advantages, but optimizing them requires more than just selecting a serotype (virus variant). It necessitates a comprehensive strategy that links promoter design, vector architecture, and distribution context.

In a recent Cell and Gene Therapy Insights webinar, Dr. Abhilasha Gupta, Senior Application Scientist at Vector Biolabs, discussed how researchers can improve accuracy and efficiency in disease modeling and therapeutic discovery using targeted viral vectors. The session highlighted practical approaches for designing AAV and adenoviral systems that align with experimental goals and real-world examples.

The fundamentals of targeted viral vectors for disease modeling – matching vector to purpose

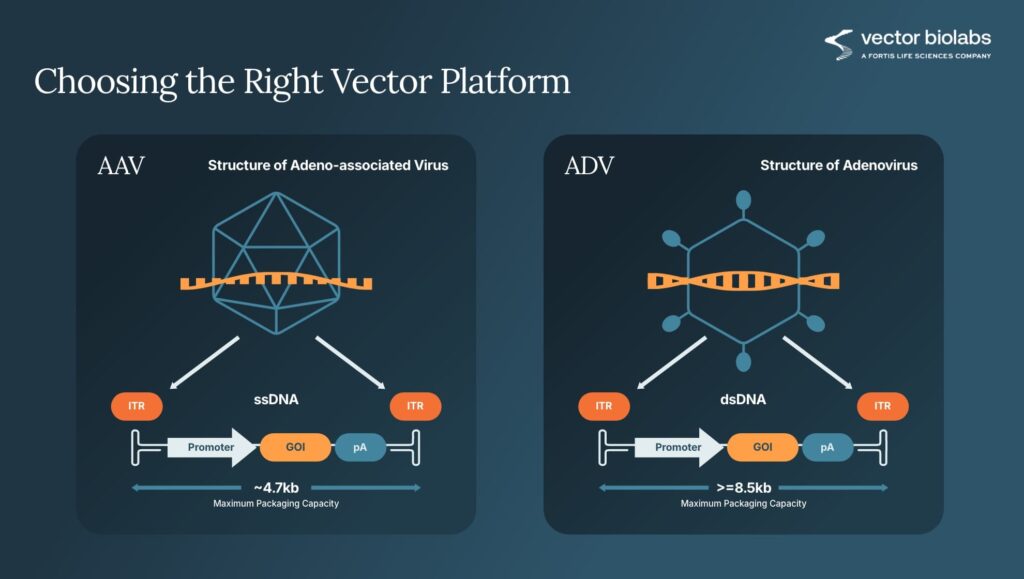

Each vector platform has distinct capabilities. Adenovirus (AdV) provides broad tropism and rapid, high-level expression that lasts only days to weeks, ideal for short-term studies or assay development or vaccine applications. Adeno-associated virus (AAV), on the other hand, supports long-term expression with exceptional safety and low immunogenicity, making it the preferred choice for long-term in vivo models for gene therapy, gene editing or target tissue delivery. AAV has a smaller packaging capacity compared to adenovirus (Figure 1).

Broad tropism is the ability of a pathogen, such as a virus, bacterium, or parasite, to infect and grow in a wide range of cells and tissues within a host, or even across multiple different species. Viral tropism is the specificity of a virus for a certain host cell type, tissue, or species.

A variant, self-complementary AAV (scAAV), accelerates gene expression by bypassing the second-strand synthesis required by single-stranded AAV, though its packaging capacity drops to roughly 2.3 kilobases, half the capacity of standard AAV. Choosing among these formats depends on insert size, required expression kinetics, and biological system (Figure 2).

Promoter–capsid pairing – a key design decision

An effective vector design starts with identifying the right capsid–promoter combination. The capsid defines which cells a vector can enter, while the promoter determines where and how strongly the gene is expressed. Dr. Gupta emphasized that there is no universal vector; performance depends on the promoter–capsid combination, the cell environment, and the delivery route.

For example, an AAV serotype that crosses the blood–brain barrier might work well with in vivo neurobiology models but show poor performance in cell culture if receptor expression is absent. In this case, an AAV9 with human synapsin promoter crosses the blood–brain barrier and drives strong neuronal expression in vivo yet performs poorly in HEK293 cells due to missing receptors. Similarly, a liver-specific promoter could drive strong expression in primary hepatocytes but demonstrate little activity in immortalized cell lines. Researchers might see this in the case of AAV8 with a liver-specific TBG promoter that is optimal for liver targeting in vivo but exhibits low activity in immortalized hepatocyte lines. These examples underscore that in vitro and in vivo results are rarely interchangeable. The biological environment, receptor availability, and route of administration must all shape vector selection.

Addressing difficult cell types

Microglia, the immune cells of the brain, are difficult to transduce and are one of the persistent challenges in vector design. Native AAV serotypes display limited efficiency, while specialized promoters often fail outside their natural environment. Advances in capsid engineering, such as inserting targeting peptides into the receptor binding region of the AAV capsid are expanding tissue tropism (Stamataki et al. 2024), and Dr. Gupta noted that pairing these promoters with microRNA detargeting elements can improve selectivity by suppressing off-target neuronal expression (Dhungel et al. 2018, Geisler & Fechner 2016). microRNA detargeting is a strategy used to silence transgene expression in unwanted cell types—even if the viral vector physically enters those cells. It works by inserting short microRNA (miRNA) target sites into the 3′UTR of the transgene cassette (Wang et al. 2024).

Delivering large genes beyond AAV’s size limit with dual AAV systems

Delivery of large genes, multicomponent expression cassettes or CRISPR components, can be restricted by the 4.7kb packaging limit in AAV’s. Dr. Gupta described three methods to overcome this constraint:

- mRNA trans-splicing, allows for reassembly at the mRNA level by using two vectors that each carry a portion of the gene and splice donor/acceptor sites.

- Homologous recombination, which reconstructs a gene at the DNA level by utilizing overlapping sections across vectors.

- Protein trans-splicing, following translation, split inteins self-ligate the encoded protein.

These dual- or triple-AAV systems allow larger genetic payloads and more sophisticated constructs, but their effectiveness depends on co-delivery to the same cell and balanced vector ratios.

A collaborative case study used dual AAV9 CRISPR vectors to downregulate the serotonin receptor 5-HT2A in mice via intranasal delivery. The project achieved reduced receptor expression and measurable behavioral improvement, demonstrating the real-world potential of dual-vector systems (Rohn et al. 2023, Rohn et al. 2024).

Quality and validation

Quality control must be just as strict as vector design precision, since even minor impurities or inaccuracies in a viral preparation can fundamentally alter how the vector behaves in vitro or in vivo. There are several techniques now in use including SDS-PAGE to test capsid purity, light scattering to measure aggregation, and using qPCR or digital PCR for measuring titer.

Before proceeding to sophisticated payloads, Dr. Gupta emphasized the significance of using control viruses, such as Vector Biolabs’ dual-GFP constructs, to confirm co-transduction. Early controls avoid misunderstandings, such as assuming a dual-AAV system failed because the biology is incorrect, when in fact only one vector entered the cell, or misinterpreting weak expression as promoter failure rather than low multiplicity of infection (MOI) or poor vector quality. and save time. In addition to ensuring consistency, a well-designed QC procedure increases trust in the biological data obtained from each investigation.

In summary – smarter vector design for better disease models

Creating high titers is no longer the only goal of modern viral vector design; engineering specificity, control, and scalability are also critical. Researchers can use targeted viral vectors for disease modeling and therapy discovery by aligning vector type, promoter, and capsid with biological context and validating each step with strong analytics, advancing gene-based innovation toward the clinic.

From design to delivery – the Vector Biolabs approach

Founded at the University of Pennsylvania more than two decades ago, Vector Biolabs is a global provider of ready-to-use viral vectors for preclinical research. The company provides end-to-end custom viral vector production from vector design and cloning through packaging, purification, and bioanalytics, with turnaround times as short as two to three weeks. Researchers can also choose pre-validated vectors that are available for immediate delivery.

Interested in custom vectors or off-the-shelf, pre-validated vectors? Contact Us

References

Vector Biolabs. (n.d.). Streamline disease modeling and therapeutic discovery with targeted viral vectors [Webinar]. Retrieved December 5, 2025, from https://www.vectorbiolabs.com/webinar/streamline-disease-modeling-and-therapeutic-discovery-with-targeted-viral-vectors/

Stamataki M, Rissiek B, Magnus T, Körbelin J. Microglia targeting by adeno-associated viral vectors. Front Immunol. 2024 Jul 5;15:1425892.

Rohn TT, Radin D, Brandmeyer T, Linder BJ, Andriambeloson E, Wagner S, Kehler J, Vasileva A, Wang H, Mee JL, Fallon JH. Genetic modulation of the HTR2A gene reduces anxiety-related behavior in mice. PNAS Nexus. 2023 Jun 20;2(6):pgad170

Rohn TT, Radin D, Brandmeyer T, Seidler PG, Linder BJ, Lytle T, Mee JL, Macciardi F. Intranasal delivery of shRNA to knockdown the 5HT-2A receptor enhances memory and alleviates anxiety. Transl Psychiatry. 2024 Mar 20;14(1):154.

Zwi-Dantsis L, Mohamed S, Massaro G, Moeendarbary E. Adeno-Associated Virus Vectors: Principles, Practices, and Prospects in Gene Therapy. Viruses. 2025 Feb 9;17(2):239. doi: 10.3390/v17020239. PMID: 40006994; PMCID: PMC11861813.

Haggerty DL, Grecco GG, Reeves KC, Atwood B. Adeno-Associated Viral Vectors in Neuroscience Research. Mol Ther Methods Clin Dev. 2019 Nov 26;17:69-82.

Dhungel B, Ramlogan-Steel CA, Steel JC. MicroRNA-Regulated Gene Delivery Systems for Research and Therapeutic Purposes. Molecules. 2018 Jun 21;23(7):1500. doi: 10.3390/molecules23071500. PMID: 29933586; PMCID: PMC6099389.

Geisler A, Fechner H. MicroRNA-regulated viral vectors for gene therapy. World J Exp Med. 2016 May 20;6(2):37-54. doi: 10.5493/wjem.v6.i2.37. PMID: 27226955; PMCID: PMC4873559.

Wang JH, Gessler DJ, Zhan W, Gallagher TL, Gao G. Adeno-associated virus as a delivery vector for gene therapy of human diseases. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2024 Apr 3;9(1):78. doi: 10.1038/s41392-024-01780-w. PMID: 38565561; PMCID: PMC10987683.

Naso MF, Tomkowicz B, Perry WL 3rd, Strohl WR. Adeno-Associated Virus (AAV) as a Vector for Gene Therapy. BioDrugs. 2017 Aug;31(4):317-334. doi: 10.1007/s40259-017-0234-5. PMID: 28669112; PMCID: PMC5548848.